An raibh a fhios agat? Did you know?

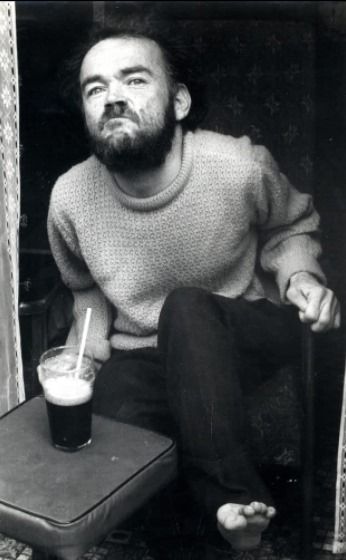

Christy Brown

The desire to realise your dreams is a tantalising torment for many of us perhaps who have to contend with the intricacies of life and the demands of modernity. One can appreciate that for a person who has to struggle with the extra demands of a disability that this can be daunting. Christy Brown’s story is legendary, his life an example of triumph over adversity, a talent that was extraordinary. His life as depicted by that brilliant actor Daniel Dey Lewis in the film ‘My Left Foot’ brought home to us perhaps the incredible efforts that Christy summoned up in order to bring forth his undoubted talent. It might also have resonated with our innermost thoughts that disability is a reality for many of our fellow citizens. But Christy was a writer, a poet, a painter and a citizen of the state equally. This short overview cannot do his story justice.

Introduction

In Ireland, some argue that we like to procrastinate when it comes to issues that authority might not rank as high on their list of priorities particularly when it comes to United Nations conventions. We might sign up to a convention but often it can take years before we ratify it. However, when we see people with disabilities protesting outside Leinster House (Irish Parliament), it brings the reality home to us that disability is a serious issue in our country. People looking for the reinstatement of a basic necessity while money is being poured down the proverbial drain in other areas begs the question; why is disability such a taboo issue? The Republic of Ireland is just shy of one hundred years old and yet even in our capital city a disabled person will encounter obstacles when trying to negotiate roads and footpaths. But even in the reality of today we are all entitled to look for a better tomorrow.

Christy Brown arrived in the early chapters of the New State in June 1932, Ireland having gained independence from Britain a mere ten years before hand. It was a period of great change; great hardship for ordinary people and the Browns were no different. Christy was one of twenty two children (nine died in infancy) that came into the world. It was after a short period of time that complications arose and Christy would be diagnosed with cerebral palsy. The conventional wisdom from family and friends alike was to place Christy in a home. However, his mother, Bridget would not countenance this and she opted to look after the boy at home. To quote from Brown (1954 p13) … “I know my boy is not an idiot. It is his body that is shattered, not his mind. I’m sure of that”.

His family lived in a Corporation house at the time, categorised as working-class. His father Patrick was a bricklayer and several of his sons would take up the trade of the trowel. Christy’s mum had a different direction in mind for Christy which she, in no uncertain terms was the inspiration for, one could argue. He responded by writing the initials of his name on a blackboard with a piece of chalk lodged between the toes of his left foot, this at the age of five. His mum thought him the alphabet. His genius was his determination to prevail; the talents that he provoked a testament to the love of his mother; his siblings were the cement that solidified his place in the bosom of the family. Christy suffered from all of the human frailties that are the lot of many: he wasn’t always perhaps the most pleasant of people to be in one’s company but he was Christy Brown. Writing in The Irish Times Hanna (1999) puts it more transparently perhaps when stating: “there was a certain ruthless eye for survival in Christy which meant people and institutions were discarded when they had served their purpose”.

A collection of letters that came into the possession of one Anthony Jordan, former principal of the Cerebral Palsy school in Sandymount which Brown attended, and which formed part of a biography penned by Jordan, also comes to the attention of Hanna (1999). The book entitled ‘Christy Brown’s omen’ is based on that collection of private letters revealing the desires and longings of a man seeking a sensual relationship and much more. But there is another story within the story of Christy Brown. That story is one of tenderness, toleration and togetherness. Ireland may well have lost the standard Céad Míle Fáilte welcome that categorises where we come from, some will argue, but family and community spirit still burns bright even today. For the Brown’s, but particularly in the presence of Christy’s mum Bridget, her determination and bravery shines through. There is a Bridget Brown in every town and city, small village or hamlet in Ireland. There is a universal connectivity that inspires people to achieve the impossible, to walk, crawl or climb on the shoulders of the truly inspirational. For people with a disability they are their own inspiration but sometimes they need a helping hand. Where else can we get inspiration?

"So many of our dreams at first seem impossible, then they seem improbable, and then, when we summon the will, they soon become inevitable." – Christopher Reeve

In Brown’s case there were a number of people who helped him to achieve a degree of independence. Katriona Maguire nee Delahunty who was a social worker, befriended him from an early age up to the time of his demise, according to Hanna (1999). To aid him in improving his speech there was a doctor Patricia Sheehan. Doctor Robert Collis helped to unlock Brown’s potential by encouraging his creativity. Being an author himself he helped Brown to publish some of his work. On the minus side there is the argument that his marriage to Mary Carr had a destabilising effect on Brown. Taking him away from home to live in Kerry and then to England may well have been unsettling with tales of him being left for long periods in isolation not having helped. An American lady, Beth Moore would also enter his orbit and became a regular penfriend as it were. She it was who was the driving force in helping him produce his second book 'Down All the Days'.

My Left Foot.

Using the book as our road map as it were, there are a number of passages that are very inspiring; the words are Christy’s no doubt. But being a painter and an author gave him an advantage one could argue. Simultaneously we can draw on a critical analysis by Martin Collins (2012) to cast an enquiring eye as it were… He points to the other obstacles that Christy possibly faced in the Ireland of the fifties. Conservatism reigned with the Church having more than an influence on publications that it deemed unsuitable for public consumption. Collin’s (2012) goes on to comment on Christina Hambleton’s biography as perhaps loking more indepth at Brown's private life. warts and all, as compared to Sheridan's portrayal in ' My Left Foot '.

Collin’s also remind us that Christy in both his books; My Left Foot and Down All the Days, placed the taboo issues of his time under the microscope of public opinion. Brown encapsulated those issued to include: the arts, the working class, the role of the mother, alcoholism, domestic abuse, sex and the impact of siblings on a person’s life. However, Collins ( 2012) quoting from sources in his Critical Analysis makes the point that Brown’s ‘Down All the Days’ sees as a departure from the conventional treatment afforded to disability in putting the wheelchair bound person in the central role of the book, not as part of the supporting cast as it were. In this context he marks Brown’s work as being ahead of its time albeit acknowledging that Helen Keller’s story preceded Brown’s by a year. Her book, Helen Keller: 'The Story of my Life' is considered as seminal in the discourse related to disability.

Collin’s also remind us that Christy in both his books; My Left Foot and Down All the Days, placed the taboo issues of his time under the microscope of public opinion. Brown encapsulated those issued to include: the arts, the working class, the role of the mother, alcoholism, domestic abuse, sex and the impact of siblings on a person’s life. However, Collins ( 2012) quoting from sources in his Critical Analysis makes the point that Brown’s ‘Down All the Days’ sees as a departure from the conventional treatment afforded to disability in putting the wheelchair bound person in the central role of the book, not as part of the supporting cast as it were. In this context he marks Brown’s work as being ahead of its time albeit acknowledging that Helen Keller’s story preceded Brown’s by a year. Her book, Helen Keller: 'The Story of my Life' is considered as seminal in the discourse related to disability.

There is a simplicity but sincerity in Brown's words but equally he manages to illicit the inspiration that finds direction in the contours of his creations. In 'My Left Foot' chapter eight, page eighty, he reflects on the disillusionment and despondency that is engulfing him as he no longer gains succour from the pursuit of painting. His predictament is choking him, his envy of the able-bodied as it were, is all absorbing. He decides on helping himself to end an existance that no longer has any meaning. " As a child I had cried bitterly when I became conscious of my own crippledom. I didn't cry now- I hadn't the comfort of tears . All my agony was inside". But that moment, when he had contemplated the unthinkable passed and he followed the trajectory of his star.

Christy Brown - Background Music

Yet my Liffey dreams were just as sweet

As those in a Wicklow valley,

And my heart was first forged in Merrion Street

And blinded with love in Bull Alley.

Christy,Burl Ives and Roses

His development as a writer took on a new departure with the intervention of Dr.Collis again. On this occasion Collis organised a concert in Dublin in aid of cerebral palsy and invited Christy and family. He managed to persuade Burl Ives to provide the musical entertainment but had a proposition for Christy. Rather than Collis as he put it, make a speech for about an hour on cerebral palsy,it would be better he thought coming from Christy. To that end he would read the first chapter of 'My Left Foot' at the concert, which Brown had recently just completed.The event took place in the Aberdeen Hall of the Gresham Hotel Dublin. When Burl Ives had completed his set with customary encores, it was left for Collis to take the floor with Christy and his parents beside him. The doctor read the chapter from Christy's autobiography. Were people were still buzzing from the musical melodies provided by Ives, a hush descended on the gathering. Some people were in tears. Then according to the script a crescendo of applause erupted. A bouquet of red roses was presented and very appropriately went to Brigid, Chrsity's mum. He would be devasted when she later died.

Conclusion

Although he mentions he did contemplate suicide apparently it is said that he died from getting food lodged in his throat. God wasn’t a bricklayer is a throw- back to a time when innocence reigned supreme…It is interesting that today his work doesn’t seem to resonate with the same force as heretofore. He was recognised by some as being in the pantheon of great Irish writers. Luckily some of his work has been preserved in the Little Museum in Dublin. In the real Ireland of the Welcomes that is occupied by the ordinary people, Christy’s star will never wane. We see many people confined to the chariot of torment or perhaps that is being unkind. However, might it be fair to say that Christy Brown proved that everything is possible; no matter how high the mountain. Christy loved to listen to Chopin. His brothers toured the streets of the neighbourhood with Christy in tow stuck into his trusty boxcar. He saw the world in a different light but in the glow of the light that he brought to so many people. The Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities was signed by Ireland in 2007 but wasn’t ratified until 2018. Christy died on the 7th September 1981 at the age of fourty nine in Somerset England.

Antóin Ó Lochraigh. Bard & Soloist

Bibliography

Brown.C. (1954) My Left Foot. Collins Educational. London UK.

Browb,C. ( 1973) Background Music. Secker and Warburg.UK.

Collins.B. (2012) Christy Brown’s Depiction of Disability in My Left Foot and Down All the Days. A critical Discourse Analysis.

Hanna.J. (1999) A legend in his own letters. The Irish Times, Dublin Ireland.

Moran.S. (2013) Great Irish People. Liberties Press. Terenure, Dublin Ireland.

Reeve. C. Quotation. So many of our dreams…

You tube. Christy Brown, Irish artist. Brief Interview from 1962. Accessed 17th June 2021.

What You Can Expect

A walk through Dublin City in the company of a native Dubliner with the emphasis on history, culture and the great Irish ability to tell a story and to sing a song. In addition, and at no extra cost an actual rendition of a self-penned verse or perhaps a spot of warbling. I'd like to share my love of history with you, after all the past is our present and should be part of our future.

About The Tours

Tours are in English, with Irish translations, where appropriate. I also speak Intermediate level Dutch. Duration: 3 hours approx., with a short break in-between. Tour prices and booking options are available in the booking section.

The contact hours are Monday to Sunday, 09:00 - 20:00 IST.

Special Options

We can also arrange a half-day private tour for a maximum of twelve people. This incorporates a collection of parts of our three Tours combined. Tour duration 4-5 hours approx. A break for refreshments in between. Group of 2: €50 per person, Group of 3: €30 p.p., Group of 4 or more: €25 p.p. Refreshments: €10 approx. (This is an extra). Please contact us for details.

Copyright ©2025 Tailteann Tours

Designed by Aeronstudio™