An raibh a fhios agat? Did you know?

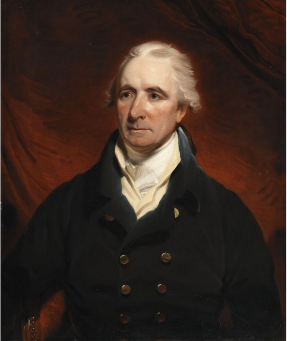

Henry Grattan

Throughout the history of the oft times strained relationship between Ireland and England or even Britain, the name of Henry Grattan is remembered as a great parliamentarian, orator and pursuer of rights for all of the people of Ireland. His critics might say that he was for the maintenance of the link with England but did subscribe to Home Rule. He was not alone in that endeavour one might argue. Today we still recall the oft quoted ...Grattan’s parliament. Whether he deserves that accolade remains perhaps the subject of interpretation. He opposed the Act of Union but did advocate maintenance of the link with Britain. His focus was on seeking the liberalisation of Irish trade free from the restrictions imposed by England. Was he a political opportunist, a royalist or simply someone who was a fair weather friend to whatever the situation demanded?...or were his egalitarian credentials justified? Hopefully we can shed some light by looking back briefly at his career.

Introduction

An Irish parliament had been established in the 13th century. This put Ireland in the ranks of the few European countries who had achieved this aim. However, it was essentially a parliament that represented the few as opposed to the alienation of the many. In essence while it carried the moniker of the ’Irish Parliament’ it was subservient to England. This meant in effect that its direction would be dictated by the interests of the neighbouring island. It would take a revolt by the colonists in North America in the 18th century to allow for a degree of political flexibility on behalf of England. Coquelin (2019) is adamant in his declaration of the parliament, made up as it was later of members of the dominating Anglican doctrine that was…as being absolutely corrupt. England’s difficulties in North America saw the withdrawal of thousands of soldiers based in Ireland to meet the challenge posed. This resulted in thousands of Irishmen enlisting in the Volunteers, a force assembled to protect Ireland from the potential of an invasion. This would become a bargaining chip which Grattan would exploit.

The Legal Eagle

Henry Grattan was born into a well off family on Fishamble Street in Dublin in July 1746. Like his father and many from the Ascendency classes he would follow the path of the legal profession. In the 18th century in Ireland the methodology used was to purchase ones way into the ranks of the established order. The monetary cost of such was beyond the reach of the young Grattan which Kelly (1993) puts at £1,500-£2,500. Fortune would shine on the young pretender when owing to the death of one Francis Caulfield MP for Charlemont, his brother Lord Charlemont offered the role to Grattan which he duly accepted. As a consequence Grattan took his seat in the Commons on 11 December 1775, according to Kelly (1993). Curiously his father hadn’t bequeathed him the family seat at Belcamp when he died in 1766. His father having followed the well-trodden path to legal security expected his son to follow suit. The younger Grattan would ultimately follow his own star. Despite his achieving the necessary qualifications Henry was more at home in the pursuit of politics.

While the elder Grattan when viewed by Kelly (1993) is seen as old-fashioned Whig who supported the maintenance of the exclusionist polices against Catholics that prevailed at the time, this didn’t find favour with his son Henry, Kelly (1993) opines. The magnetic pull that was the power of politics saw him drawn to the House of Lords where he spent countless hours listening to and studying the technique and style of people like Edmund Burke and the Earl of Chatham. At play during this period according to Kelly (1993) was the question of the term of office, if you would, of the Irish parliament. People like Charles Lucas wanted this limited to a period of seven years. This was also the carrion cry of one Henry Food. There was no limitation on the life span of the Irish parliament as this was determined in essence by the longevity of the reigning monarch. Flood in particular was seen as an opponent of the status quo in this regard and spoke out eloquently and formidably and was seen as the de facto leader of the opposition. However, it should be remembered that the political climate that the actors concerned operated in where by all accounts a quasi-political entity in name only. The politics at play here had been copper-fastened by Poyning’s Law.

Poynings Law

In order to comprehend the machinations at play it might be beneficial to revert back to the political reality that effectively prevailed in Ireland up to the 15th century. Ireland had been ruled by England from the 12th century but it maintained its control in a rather haphazard way. Ireland had not been defeated and indeed the counties outside of the ‘Pale’ were still to a degree under the control of the Irish Chieftains. However, a law was passed in Drogheda in 1494 which became known as ‘Poynings Law’ after the chief governor to Ireland, Sir Edward Poyning which if you would copper fastened English control in Ireland, administratively at least.In effect any Bill passed by the ‘Irish’ parliament had to go to England for approval and ratification by the English parliament. This situation would remain in situe until 1782. Events in the American colonies would fundamentally change and alter the situation in Ireland. In the interim the furtherance of colonisation was reenergised under Henry VIII in the 16th century. He conveniently awarded himself the kingship of Ireland. The conquest would be continued under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell in the 17th century.

The Patriots

Olivier Copquelin (2019) opines that Grattan did succeed in achieving “almost complete legislative autonomy in 1782, autonomy through which the Irish Parliament was henceforward commonly dubbed as “Grattan’s Parliament”. Interestingly he subscribes this achievement to parliamentary and paramilitary agitation. He subscribes this development initially to the emergence of a parliamentary opposition which would carry the name of “Patriots”. This grouping if you would were led by Charles Lucas and Henry Flood. This awakening occurred in the mid eighteen century but it was the arrival of Grattan on the political stage in 1775 that would lend weight to their endeavours, according to Colquelin (2019). It should be pointed out that Flood and Lucas sought legislative autonomy as well as a reduction in the term of office of the Irish parliament to seven years along with greater control of government expenditure. We referred earlier to Copquelin's (2019) and his sentiments regarding Grattan's ' almost complete legislative autonomy in 1782': Kelly (1993) would appear to echo those sentiments when anouncing that the Hose of Commons agreed to award Grattan the sum of £50,000 for his efforts.This act of benevolence Kelly (1993) describes as " highlighting the sense of euphoria that characterised the national mood in the early summer of 1782". One might question such generosity by a parliament that appears to have had a perpetaul relationship with indebtedness and how this was seen as in the national interest, when Catholics were excluded from engaging in society in the main.

Henry Flood

The relationship between Grattan and Henry Flood appears to have been less than amicable. The events of 1776 might be viewed as the precursor but the political manouverings continued apace. Indeed, it got to the stage that a duel was proposed by Flood. However, the nucleus for this lay in the fact that Grattan had been upstaged as it were by Flood in his condemnation of Grattan's incomplete legislative independence from Britain along with the 1776 clash, something that left a deeply wounded Grattan on the scent for revenge and to which we will return. Kelly (1993) also portrays Flood as being the “most talented opposition spokesman”. Kelly (1998) writing in History Ireland again visits this point and is fulsome in his praise of Flood the parliamentarian. What he points to as being Flood’s shortcomings were the lack of an ability to curry favour among his fellow MPs and perhaps a tendency to distance himself from the tedium of life that lesser mortals inhabited, so perhaps someone viewed as 'overbearing' as Kelly (1998) suggests might be an apropriate way of describing Flood.

His decision in 1775 to accept the position of vice-treasurer ship from the Irish administration would also prove less than inspiring. This effectively took him out of the equation, a vacuum that other’s in the ranks of the Patriots would fill. The perception at least was that he was working in tandem with Dublin Castle. His five year term as office holder would come to an end in 1781 when he failed to support the Castle in the House of Commons. He once again joined the ranks on the opposition benches but to much hostility from his erstwhile colleagues. Flood criticized Grattan’s parliament and the parliamentary concessions of 1782 and argued that England had not relinquished its controlling influence over Ireland. Such pronouncements went down well within the ranks of the “politicised Protestant public”, according to Kelly (1998) no more so than when Westminster recognized the ‘legislative independence of the Irish parliament’ in 1783. Grattan also worked closely with the Volunteers at this time but was opposed to any attempt emanating from some quarters, to allow Catholics enter the political process. Changing the status quo and thereby Protestant ascendancy was not something he could countenance.

Grattan v Flood

The rivalry If one can call it that between Grattan and Flood came to prominence in 1776 at the out break of hostilities between Britain and the colonists in North America. According to Kelly (1993) Flood supported the decision of the government to embargo Irish exports to the colonies as a “necessary action”. Grattan in turn denounced the embargo as illegal dismissing Flood’s remarks as ’the tyrant’s plea’, Kelly (1993 pg9) continues. Such utturances brought Grattan to the attention of Dublin Castle. The general election in 1776 essentially resulted in a split in the House of Commons. Kelly (1993) opines with Grattan using the government’s difficulties in America to pursue the reforms that the Patriots were in pursuit of. He repeatedly focused his ire on the failure of ‘successive governments to balance the kingdom’s budget’. His tirade aimed at the British government was seen as quite provocative when blaming them for prohibiting their Irish equivalent from reducing expenditure on pensions and military commitments. Furthermore he accused the ‘English administration of “corrupting the constitution and who have lost the empire to Great Britain”.

The rivalry If one can call it that between Grattan and Flood came to prominence in 1776 at the out break of hostilities between Britain and the colonists in North America. According to Kelly (1993) Flood supported the decision of the government to embargo Irish exports to the colonies as a “necessary action”. Grattan in turn denounced the embargo as illegal dismissing Flood’s remarks as ’the tyrant’s plea’, Kelly (1993 pg9) continues. Such utturances brought Grattan to the attention of Dublin Castle. The general election in 1776 essentially resulted in a split in the House of Commons. Kelly (1993) opines with Grattan using the government’s difficulties in America to pursue the reforms that the Patriots were in pursuit of. He repeatedly focused his ire on the failure of ‘successive governments to balance the kingdom’s budget’. His tirade aimed at the British government was seen as quite provocative when blaming them for prohibiting their Irish equivalent from reducing expenditure on pensions and military commitments. Furthermore he accused the ‘English administration of “corrupting the constitution and who have lost the empire to Great Britain”.

Volunteers

In order to meet the deteriorating situation in its American colonies England had to withdraw its sizeable contingent of troops in Ireland and dispatch them across the Atlantic. In order to meet any potential threat in Ireland they allowed the establishment of a Volunteer force. Rumours of a French invasion were rife. However, there was no money in the coffers to establish such. Protestant gentlemen took it upon themselves to organise hence the emergence of the Volunteers. The government viewed this with some apprehension as this force was in essence out of the control of Dublin Castle.

Grattan further fuelled the fires by participating in the non-importation campaign of goods from England specifically designed to promote home consumption as Kelly (1993) suggests or what we might call today as a …Buy Irish campaign. Further pressure was applied by the Patriots according to Kelly (1993) by the display of the ‘Dublin Volunteers’ at parliament buildings in full military preparedness with placards demanding …Free Trade or Revolution. Interestingly this event took place on the 4th of November, William of Orange’s birthday. They also refused to support Dublin Castle’s request for full implementation of taxes. What would follow however, owing to the intransigence of the Patriots was the opening up of colonial trade to Iris goods a key demand of the Patriots. The parliament buildings were situated in College Green, literally a stone’s throw from Dublin Castle.

The Ascendancy

What comes across quite distinctly in Kelly’s analysis of the situation in 1792 was Grattan’s attempts to appease both camps in the machinations at play at that time. Catholics were adamant that the ‘concessions’ on offer didn’t go far enough; they wanted the franchise while Protestants wanted their position or Protestant ascendancy maintained. At play here was also the not too inconsiderable fact that fearing an invasion from France it was important to keep Catholics on board. By this time it was clear that Grattan was steering a middle ground; that of maintaining the position of monarchical benevolence coupled with maintaining the privileged position of the Protestant minority with some semblance .of ‘parity of esteem’ being bestowed on Catholics.And so it lumbered on. The actors were playing to the gallery, winning comcessions that pleased some while alienating the majority while events were moving inexorably towards confrontation and the United Irishmen.

The 1798 Rebellion

Grattan was accused by many within the ranks of the ascendancy of involvement in the rebellion. Grattan had decided in 1797 to disengage from the House of Commons. His attempts to bring change as in parliamentary reform with access to the disenfranchised majority caused him great anguish, Kelly (1993) laments. With his disillusionment of the war with France and the treatment of those with a United Irishmen sentiment in Ulster by General Lake, he could see no alternative but to withdraw from politics. While not agreeing with the direction and thrust of the United Irishmen, he had found occasion to both socialise and work with them, Kelly (1993) continues. At the outbreak of hostilities in May 1798 Grattan was in England. Despite this he was accused by a Dr. Patrick Duigenan of complicity with the United Irishmen on the basis perhaps of an informer who maintained that he had taken the oath of that organisation.

Consequently he was banished from the Irish Privy Council by George III and expelled from the Dublin Guild of Merchants. The events of 1798 had propelled the possibility of the union of Britain and Ireland which the Protestant Ascendance were in favour of while remaining opposed to Grattan’s attempts to bring a more inclusive situation to bear which was the road he had attempted to travel since 1782. Grattan’s parliament if that title be justified was in its death throes. Reputation ally he had been dealt a severe blow so much so it appears that talk of a duel with Duigenan had been mooted but didn’t materialise. Inclusivity was put on the back burner. From Grattan’s perspective he had no sympathy with the United Irishmen or what remained of them and indeed we can glean his antipathy towards them when digesting the remarks attributed to him by Kelly ( 1993) when describing them as the ‘separation party’. This further cements his stated monarchical sympathies perhaps.

The Act of Union

He opposed the Act and as a consequence ended up having to fight a duel with one Isaac Corry, a staunch pro-Union MP. The upshot was that he wounded Corry in the arm, a situation that brought him much acclaim throughout the country, according to Patrick Geoghegan (2009) writing in The Irish Times. Much has been written and spoken of in terms of the Act of Union and how it came about about.The bestowing of financial windfalls and titles on the members of the dependent parliament are the subject of legend and continue to cast a shadow over one of the most controversial episodes in Irish history. The conventional wisdom is that the England having failed to win the first vote in 1799 resorted to bribery which eventually won the day. This again caused deep resentment amongst the Protestant minority who had depended on the Penal Laws as a buffer againg Catholics attaining positions in the political firmamant. Grattan opposed the Act of Union.

Conclusion

Henry Grattan lived through a period of immense upheaval and change both in Ireland and internationally. The French revolution caused shockwaves in the imperial parlours of pleasure that were monarchical in their makeup. The ruling classes saw this as a challenge to their legitimacy one could argue. The revolt by the colonists in North America further challenged their control and then in Ireland the drums of discontent were banging ever louder. His critics might argue that he was a staunch advocate of the Ascendency classes and for the maintenance of the link with Britain. Others will argue that he sought a middle ground that gave some rights to Catholics who in essence had none prior to his endeavours. We have attempted to throw some light on Grattan’s life in politics such as it was. From a non-partisan perspective it could be argued that he was a sincere individual; practical from a political perspective but based on his record, a parliamentarian of some magnitude. The argument, deserving or not, as to his being credited with the moniker’ Grattan’s Parliament’ I will leave for others to decide.

Antoin O Lochraigh

Bard & Soloist

Bibliography

Aldous. R. Great Irish Speeches.

Coquelin. O. (2019) Grattan’s Parliament (1782-1800): Myth and Reality. University of Western Brittany, Brest, France.

Dickson. D. (2015) Dublin The making of a capital city. Profile Books Ltd. London UK.

Geoghegan P. (2009) Daniel's deadly duels. The Irish Times. Dublin Ireland.

Kelly.J. (1993).Henry Grattan. Historical Association of Ireland. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk Ireland.

Kelly J. (1998) Henry Flood: Patriots and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Ireland. History Ireland. Ireland’s History Magazine, Dublin Ireland.

Lysaght. C. (2020) Henry Grattan looms large over modern Ireland. The Irish Times. Dublin Ireland.

Shee.M.A. (18th Century) Portrait of Henry Grattan. National Gallery Ireland. Accessed on Wikipedia 9th July 2021.

What You Can Expect

A walk through Dublin City in the company of a native Dubliner with the emphasis on history, culture and the great Irish ability to tell a story and to sing a song. In addition, and at no extra cost an actual rendition of a self-penned verse or perhaps a spot of warbling. I'd like to share my love of history with you, after all the past is our present and should be part of our future.

About The Tours

Tours are in English, with Irish translations, where appropriate. I also speak Intermediate level Dutch. Duration: 3 hours approx., with a short break in-between. Tour prices and booking options are available in the booking section.

The contact hours are Monday to Sunday, 09:00 - 20:00 IST.

Special Options

We can also arrange a half-day private tour for a maximum of twelve people. This incorporates a collection of parts of our three Tours combined. Tour duration 4-5 hours approx. A break for refreshments in between. Group of 2: €50 per person, Group of 3: €30 p.p., Group of 4 or more: €25 p.p. Refreshments: €10 approx. (This is an extra). Please contact us for details.

Copyright ©2025 Tailteann Tours

Designed by Aeronstudio™