An raibh a fhios agat? Did you know?

Ireland’s Nobel Prize Laureates - George Bernard Shaw

This is the first in a series of articles giving an overview of Ireland’s four recipients of the Nobel Prize for literature. True to form we start with the second winner of that coveted accolade, one George Bernard Shaw. The other recipients were: William Butler Yeats, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney.

Shaw doesn’t sit comfortably with the accepted greats of Irish literature such as: Oscar Wilde, James Joyce, Yeats, Beckett and so on, at least that might be the perception. However, in terms of drama and his prolific outpourings that spanned two World Wars and countless other world phenomena, Shaw perhaps rates as one of the greatest thinkers of his time. This then is the first of four articles on Ireland’s path to universal recognition as a haven for literary genius one could argue. A newly released book by David Ross (2020) on the life of George Bernard Shaw (GBS) gives an excellent insight into the life and times of the great man. With extracts from some of his less well known work and other contributors, this is an attempt to look at the world of the entertaining but always controversial G.B.S. as he was also called.

Introduction

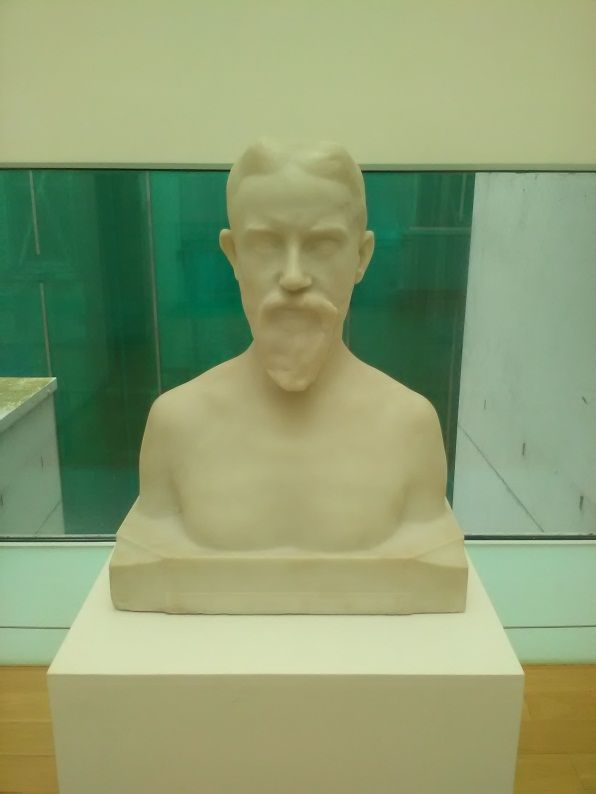

George Bernard Shaw was Ireland’s second recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature which he received in 1926. He is perhaps best remembered for his exertions as a dramatist and composed over sixty pieces of work. He is the only winner of the Nobel Prize for literature and the recipient of an Oscar for his adaptation of Pygmalion which would become the much loved film entitled ‘My Fair Lady’. Shaw was an interesting fellow from many perspectives one could argue. Born in Synge Street Dublin in July 1856, he came from a modest background by all accounts. He was one of three children and though not well off they could still afford to have servants. Looking after the boy and his two sisters fell under the stewardship of the servants. This apparently would leave a long lasting impression on the boy who suffered from a lack of parental love it is suggested.

George Bernard Shaw was Ireland’s second recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature which he received in 1926. He is perhaps best remembered for his exertions as a dramatist and composed over sixty pieces of work. He is the only winner of the Nobel Prize for literature and the recipient of an Oscar for his adaptation of Pygmalion which would become the much loved film entitled ‘My Fair Lady’. Shaw was an interesting fellow from many perspectives one could argue. Born in Synge Street Dublin in July 1856, he came from a modest background by all accounts. He was one of three children and though not well off they could still afford to have servants. Looking after the boy and his two sisters fell under the stewardship of the servants. This apparently would leave a long lasting impression on the boy who suffered from a lack of parental love it is suggested.

He was of Anglo Irish stock his family having originally come from England. Having worked as a clerk for an estate agency for the princely sum of eighteen shillings a week in Molesworth Street, he followed his mother to London at the age of twenty. It would take time for him to become accustomed to his new surroundings and for his work to attain the recognition which he so craved. He initially contrived to write several novels none of which achieved the goal of universal recognition. He remained a teetotaller all his life and a confirmed vegetarian. Within the family circle he was labelled with the nickname ‘Sonny’. He considered himself a socialist and communist and is attributed with the quip that ‘he read Marx before Lenin did’. His Left leanings would not have met with parental approval one can surmise as his parents shared the view that they were of the Protestant Ascendency elite.

By 1890 however, his star had risen somewhat. His first claim to fame was with the drama ‘Arms and the Man’. As a journalist he had established himself commenting on political and social issues along with his critique in the areas of music and drama. As an intellectual he also became quite accomplished. Like many artists of his time in Ireland Shaw had to establish his credentials in England albeit he maintained more than a passing interests in the affairs of his native country. He was co-founder of the Fabien Society in England. This is a socialist organisation established in 1884 for the advancement of democratic socialism. It appears that he distanced himself from the root and branch version of socialism that was the lot of ordinary working people in their endeavours with their employers. However, Shaw would arguably flirt with what O’Ceallaigh Ritchsel (2007) termed as militant Irish socialism from the 1913 Dublin Lockout to the 1916 Rebellion.

By 1890 however, his star had risen somewhat. His first claim to fame was with the drama ‘Arms and the Man’. As a journalist he had established himself commenting on political and social issues along with his critique in the areas of music and drama. As an intellectual he also became quite accomplished. Like many artists of his time in Ireland Shaw had to establish his credentials in England albeit he maintained more than a passing interests in the affairs of his native country. He was co-founder of the Fabien Society in England. This is a socialist organisation established in 1884 for the advancement of democratic socialism. It appears that he distanced himself from the root and branch version of socialism that was the lot of ordinary working people in their endeavours with their employers. However, Shaw would arguably flirt with what O’Ceallaigh Ritchsel (2007) termed as militant Irish socialism from the 1913 Dublin Lockout to the 1916 Rebellion.

He did return to Ireland in 1905 it appears at the behest of his wife Charlotte who had spent her childhood in West Cork. She was also of Anglo-Irish stock. Nicholas Grene (1985) makes the point that Shaw didn’t fit too comfortably into the world of high society amongst the Anglo’s. He was referred to as the office-boy in some circles and had married above himself. By contrast in England he was accepted as a literary giant albeit belatedly perhaps of some considerable stature. Either way this was his first visit back to his place of birth in over twenty years. One of the highlights of his visits back to Ireland was in 1910 when he visited The Great Skelligs in County Kerry. The scenery of Ireland was like nothing else on earth he is reported to have remarked.

Grene (1985) goes on to comment about his apparent dislike of his native city. Shaw found the poverty and squalor of Dublin much to his dislike Grene (1985) laments. However, he continued to work during his initial return to the land of his birth and contrived to assemble his latest work entitled ‘Major Barbara’. This put the issues of wealth and poverty in Britain at that time under the microscope. By association it also dealt with the arms race essentially between the great European powers. Despite his love-hate relationship with the city of his birth he would later be given the award of the Freedom of Dublin in 1946.

In his article on Shaw’s work, ‘Shaw responds to Shaw- Bashing’, John.A.Bertolini (2005) relates to Shaw’s reaction to the quip that Germany had to be crushed totally to which he suggested that the remedy therefore would be to kill all German women. Needless to say this compounded the problem for Shaw so much so apparently that his books were removed from the shelves of many bookstores and the gathering storm clouds grew ever darker. Ultimately however and despite his professed later admiration for Mussolini and Stalin his standing would remain undiminished up until his death in 1950. While his penchant for being controversial would become less so in the last few years of his life with less outpourings he nonetheless remained an iconic figure.

His labours did receive acclaim in Germany initially prior to his gaining prominence in England. In terms of his work Pygmalion which would later be reborn as “My Fair Lady”, this might be regarded as his most celebrated piece of work because of its box- office success. However, it was perhaps the range and focus of his work, touching on domestic and social issues along with his outpourings on the unfolding international situation as he saw it, that gave him much prominence or notoriety, depending on one’s point of view. However, Ross (2020) opines that Joan of Arc was his most popular play which is still performed to this day and for which he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1926. He was prepared to tackle the sacred cows of colonial incognizance and conservatism to which his adopted country was in harmony with, according to Ross (2020)

The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet

He also had an association with the Abbey Theatre in Dublin and Lady Gregory. This association gave him the platform to have one of his lesser known dramas staged in Dublin. The censor in England had decided that some of its contents were profane and insisted that the script be changed accordingly to which Shaw flatly refused. Despite protest stations from Dublin Castle the Abbey staged The Showing-Up of Blanco Posnet. This particular story was set in America’s Wild West as it was then called. Its subject matter was of a man being saved from the gallows by a’ lady of the night’. It premiered at the Abbey in August 1909 to a packed house with no less than James Joyce among its interested spectators.

This defiance would later be seen as a blow for artistic independence and led to a deeper collaboration between Lady Gregory, Yeats and Shaw. This episode according to Hassett (2014) gained international attention in that it challenged the authority of the king of England who according to Hassett (2014) had issued the theatrical licence or patent if you would to Lady Gregory directly. Continuing in this vein and again perhaps showing his appetite for controversy Shaw delivered a lecture at the behest of Beatrice Webb a political activist ‘On Irish Destitution’ in the Ancient Concert Rooms on Pearse Street in 1910 according to Finnegan (1994).

This defiance would later be seen as a blow for artistic independence and led to a deeper collaboration between Lady Gregory, Yeats and Shaw. This episode according to Hassett (2014) gained international attention in that it challenged the authority of the king of England who according to Hassett (2014) had issued the theatrical licence or patent if you would to Lady Gregory directly. Continuing in this vein and again perhaps showing his appetite for controversy Shaw delivered a lecture at the behest of Beatrice Webb a political activist ‘On Irish Destitution’ in the Ancient Concert Rooms on Pearse Street in 1910 according to Finnegan (1994).

Just prior to the outbreak of the Great War Shaw was perhaps at the height of his creative ability. Indeed in 1913 Shaw shared a stage in Manchester in November of that year with George Russell a Dublin poet and socialist James Connolly at the Albert Hall, were the focus was on issues such as: Suffrage, Home Rule for Ireland and the 1913 Dublin Lockout. This event was ostensibly a fund raiser for the striking Dublin workers who were engaged in a bitter dispute with their employers for wanting to seek Trade Union recognition. However, following the aftermath of serious disturbances in Dublin during which several of the protesting workers were killed after a baton charge by the police, Shaw made a speech which was viewed by some as provocative. The leader of the workers Trade Union had also been arrested. Their leader was Jim Larkin.

Shaw spoke quite trenchantly by all accounts at the arrest of Larkin and entitled his speech: ‘Mad Dogs in Uniform’. This was seen as a direct attack on the police. He was also critical of the church. He was depicted as a buffoon in the Irish press while their counterparts in England called for his arrest for incitement. Shaw had made the assertion that because of the actions of the police” that all respectable men would have to arm themselves”. That this statement has been viewed by some as a call-to-arms if you would as suggested in Ritschel (2007) is mere conjecture one might argue and would appear to be contrary to Shaw’s stated position as a pacifist.

Indeed we learn that he was actively engaged in promoting the concept of Home Rule for Ireland by way of what he called a federation of ‘the four home kingdoms’ according to Ross (2020). He was bitterly disappointed that Lloyd George the UK prime minister hadn’t nominated him to the convention on Irish Home Rule set up in 1917. The subsequent partition of the country was something he was not in favour of apparently. Events moved on of course but an interesting anecdote that Ross (2020) provided is that both he and his wife Charlotte dined with Michael Collins at Kilteragh House, a country residence two days before Collins was shot in August 1922. Shaw had supported albeit reluctantly the Treaty signed by Collins and Griffith with Lloyd George the UK prime minister in 1921.

All that notwithstanding he had nonetheless obtained a reputation as a music critic and someone who later would display an interest in the rise of Fascism. He was also forthright in his opposition to the First World War and indeed remained controversial throughout his life. One of his most illuminating essays entitled: Common Sense about the War displays a remarkable interpretation of what the outcome of that war would eventually be but equally how he interpreted the role of the victors and their treatment of Germany. He likened this with how the imperial powers had behaved towards the unfortunate actors in their global adventures. This caused great consternation and hostility towards Shaw, not just in England where he was vilified by many but also in America. He ruffled the feathers of no less than the president Teddy Roosevelt.

A passionate admire of the Soviet Union, he visited there in 1931. He was even given an audience with Stalin and was taken on carefully controlled tours of Moscow and Leningrad as it then was. He appears to have been very impressed by the Soviet system and went back to England more invigorated and passionate in his beliefs. It might be fair to say that he probably saw himself as English and most certainly within the pantheon of the great dramatists of the time he was regarded apparently as being of its higher echelons. In a very interesting article on Shaw, Bertrand Russell (1951) the English philosopher, mathematician and logician remembers him as being a quite shy individual. This he considered to be a defence mechanism devised by Shaw to hide his timidity.

Russell paints a fascinating insight into a very complex individual. While complimenting him on his wit Russell was not slow to underline what he considered to be a weakness in the man by his remark that ‘His themes were of their time but not eternal.’ He makes an interesting observation on Shaw’s adherence to his belief in strong government which probably inclined him to look at dictators in an agreeable way. Hence his admiration to some degree of Stalin and Mussolini. Russell was perhaps speaking with the benefit of hindsight. “He was incredibly clever, though not wise” is another quote from Russell about Shaw but he does in fairness give credit to him for changing public perceptions with more than a degree of comedy which perhaps his demeanour and outpourings gave credence to.

Contextually one of his more controversial plays was Geneva, a Fancied Page of History in Three Acts (1938) It describes a meeting of the International Court designed to contain the increasingly dangerous behaviour of three dictators, Herr Battler, Signor Bombardone, and General Flanco (parodies of Hitler, Mussolini and Franco) and to which the three main protagonists are summoned and who subsequently and astonishingly attend. As alluded to earlier Shaw had expressed a degree of admiration for Strongmen who he perceived as being doers if you would as opposed to the political protagonists of the conservative persuasion who were failing to address the issues of the day, chief of which was perhaps unemployment. Millions of people were unemployed at that time in Germany, Britain and America for example. As Stone (1973) alludes to, Shaw is not glorifying the actions of the three proponents of conflict but rather, particularly in the case of Herr Battler ( Hitler) demonstrating that he had brought a sense of renewal to a people that had been humiliated by the Allies in the aftermath of The Great War. This is the point potentially that Shaw was at pains to get across. Indeed according to Stone (1973) Shaw himself commented that “ Geneva is a horrible play: I went to see it the other day and it made me quite ill…But I have to write plays like Geneva. It is not that I want to”. He penned this play in 1938 just prior to the commencement of World War two.

Shaw had retired to a house in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire which he purchased in 1906. This would later be called Shaw’s Corner. He had also kept a flat in London which he would later dispense with. Following a heart attack in 1934 many had had the desire to write, rather prematurely, the obituary of the Court Jester as he was so affectionately called in some quarters. But Shaw being Shaw had work to do and kept prodigiously producing more of his art. Indeed on his ninetieth birthday a reporter interviewing him remarked that he hoped that he would be able to do so again on his hundredth. ’I don’t see why not’ replied Shaw, ‘you look healthy enough to me’. Might that be a touch of Dublin wit?

Conclusion

This overview has attempted to give a brief insight into the life and times of GBS. Some of his other great masterpieces include: John Bull’s other Island, Joan of Arc etc. which time does not allow us to delve into. However, his work remains topical if not controversial to this day. The contested fact that he doesn’t appear to resonate with the legions of fans of Irish literature as others of his status is perhaps open to interpretation. The names of Joyce, Yeats and Heaney are among the more celebrated names in the area of the humanities that sometimes lies bereft of a different kind of genius, if you are a Shavian at heart that is.

Shaw finally left the stage in 1950 at the tender age of 94. Remarkably he kept working right up to his final curtain. Did he bring a seismic shift to the staid and conservative attitude of the ruling classes in his adopted country, as Ross (2020) suggests or was he the ultimate visionary who fought against the system that he himself was a constituent part of? Paradoxical he most certainly was but even geniuses are afforded the right to change their minds.

All Great Truths begin as Blasphemies

George Bernard Shaw

Bibliography

- Bertolini. J. (2005) Shaw responds to Shaw- bashing. Vol. 25.pp 127-134. Published by: Penn State University Press

- Finegan.J. (1994) Dublin’s Lost Theatres. Dublin Historical Record. Vol. 47, No. 1, Diamond Jubilee Issue (spring, 1994), pp. 95-99 .Old Dublin Society.

- Grene.N. (1985) SHAW IN IRELAND: VISITOR OR RETURNING EXILE? Vol. 5, SHAW ABROAD (1985), pp. 45-62 Penn State University Press

- Hassett. J. (2014) Theatre programme recalls brilliant coup that helped to establish artistic independence of Abbey. The Irish Times, Dublin.

- Ritschel.N.O’C (2007) SHAW, CONNOLLY, AND THE IRISH CITIZEN ARMY.Vol.27 pp 118-134. Published by: Penn State University Press

- Ross.D. (2020) the Irish Writers George Bernard Shaw A Biography. Mercier Press Cork. Ireland. ISBN 978-1-78117-774-7

- Russell B. (1951) George Bernard Shaw. The Virginia Quarterly Review. Journal ArticleVol. 27, No. 1. University of Virginia.USA

- Stone. S.C. (1973) "Geneva": Paean to the Dictators? Journal Article the Shaw Review Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 21-29 Penn State University Press

What You Can Expect

A walk through Dublin City in the company of a native Dubliner with the emphasis on history, culture and the great Irish ability to tell a story and to sing a song. In addition, and at no extra cost an actual rendition of a self-penned verse or perhaps a spot of warbling. I'd like to share my love of history with you, after all the past is our present and should be part of our future.

About The Tours

Tours are in English, with Irish translations, where appropriate. I also speak Intermediate level Dutch. Duration: 3 hours approx., with a short break in-between. Tour prices and booking options are available in the booking section.

The contact hours are Monday to Sunday, 09:00 - 20:00 IST.

Special Options

We can also arrange a half-day private tour for a maximum of twelve people. This incorporates a collection of parts of our three Tours combined. Tour duration 4-5 hours approx. A break for refreshments in between. Group of 2: €50 per person, Group of 3: €30 p.p., Group of 4 or more: €25 p.p. Refreshments: €10 approx. (This is an extra). Please contact us for details.

Copyright ©2024 Tailteann Tours

Designed by Aeronstudio™