An raibh a fhios agat? Did you know?

Robert Emmet

In this brief overview of Robert Emmet we look at the major events in his short life, the other actors in this story and the long-term consequences arguably that stemmed from this period. Ireland at this time was enduring major changes both politically and economically. Rebellions against English rule was not uncommon and after the Act of Union in 1800 the economic impact particularly on Dublin was significant. England feared the French in the heady days of Napoleon, and the embers of the 1798 Rebellion were not fully extinguished. Wolfe Tone will be remembered as one of the leading protagonists of the 1798 Rebellion, Robert Emmet for the events of 1803.

In this brief overview of Robert Emmet we look at the major events in his short life, the other actors in this story and the long-term consequences arguably that stemmed from this period. Ireland at this time was enduring major changes both politically and economically. Rebellions against English rule was not uncommon and after the Act of Union in 1800 the economic impact particularly on Dublin was significant. England feared the French in the heady days of Napoleon, and the embers of the 1798 Rebellion were not fully extinguished. Wolfe Tone will be remembered as one of the leading protagonists of the 1798 Rebellion, Robert Emmet for the events of 1803.

Robert Emmet was born on the 4th March 1778 into a comfortable Protestant background and lived at St. Stephen’s Green Dublin. His educational background might suggest that he was a gifted child in that he attended Trinity College from the age of fifteen. He joined the college debating society where he honed his oratorical skills. However, his sojourn in Trinity would prove short-lived as he was expelled for his political affiliations, as was his elder brother before him, Thomas Addis Emmet. The French Revolution of 1789 had perhaps resonated with people who sought to forge a different path other than that of being subordinate to a colonial regime. Emmet for his part was of the view that the only way to achieve this was by force of arms. It was also just a few short years after Fitzgerald’s 1798 Rebellion. It had ended in failure but had left an indelible mark on the ruling establishment. That having been said they were taken somewhat by surprise initially at least with the events of 1803.

The situation that prevailed in Europe at that time was one of apprehension perhaps from a British perspective as they viewed Ireland being used as a launch pad by Napoleon to invade England. Nolan (2013) posits that Emmet coincided his revolt to take place in the same year as the anticipated French assistance, in 1803. Preparations for the revolt had been put in place with weapons being stored throughout the town most notably in close proximity to Dublin Castle, the nerve centre of British rule in Ireland. However, Emmet formed the view that Napoleon was not really interested in Ireland’s difficulties and so it was that on the 23rd July 1803 and through other unfortunate circumstance that the revolt began.

There were reports that the authorities had gotten wind about the revolt, albeit belatedly, and had manufactured a situation whereby the insurgents had become the recipients of a sizeable quantity of alcohol. This was to have a serious impact on proceedings. As recounted by Moran (2013) Emmet while leading one hundred of his supporters with the intention of attacking Dublin Castle, instead witnessed an attack on Lord Chief Justice Kilwarden and his nephew by some of his followers. Both were dragged from their coach and killed. The situation then deteriorated. The planned Rising petered out amidst some confusion and Emmet made his escape to the Dublin mountains. In his Review of the book: Robert Emmet A Life, Geoghegan (2003) is both critical and praiseworthy of Emmet, critical in that he laments the rebellion as a disaster, but praiseworthy in that he reflects that Emmet’s 'speech from the dock' achieved the ultimate realisation of its intention, to be forever recounted. From a historical perspective one could argue that it achieved its goal.

There were reports that the authorities had gotten wind about the revolt, albeit belatedly, and had manufactured a situation whereby the insurgents had become the recipients of a sizeable quantity of alcohol. This was to have a serious impact on proceedings. As recounted by Moran (2013) Emmet while leading one hundred of his supporters with the intention of attacking Dublin Castle, instead witnessed an attack on Lord Chief Justice Kilwarden and his nephew by some of his followers. Both were dragged from their coach and killed. The situation then deteriorated. The planned Rising petered out amidst some confusion and Emmet made his escape to the Dublin mountains. In his Review of the book: Robert Emmet A Life, Geoghegan (2003) is both critical and praiseworthy of Emmet, critical in that he laments the rebellion as a disaster, but praiseworthy in that he reflects that Emmet’s 'speech from the dock' achieved the ultimate realisation of its intention, to be forever recounted. From a historical perspective one could argue that it achieved its goal.

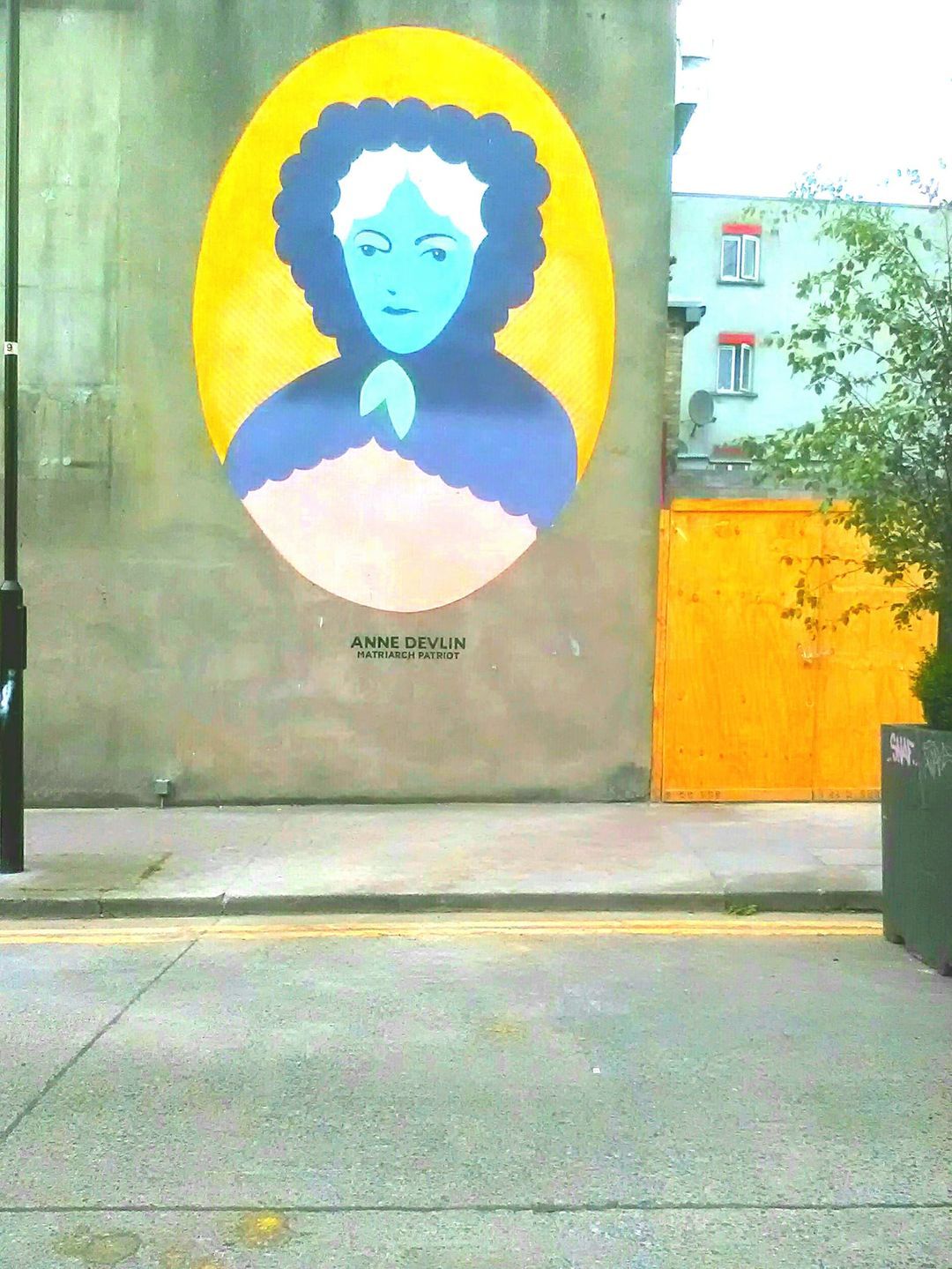

Whelan (2003) points to the futuristic language of Emmet’s epic speech and indeed that of the revolutionary per se who yearns for the advent of freedom for his or her country. The consequences of failure were evident, his rendezvous with the scaffold and its immediate aftermath the lot of the nonconformist. One could argue that Emmet met his faith with resolve. Whelan (2003) waxes lyrical about the inspiration that Emmet would invoke in people like Padraig Pearse in 1916 and in Republicanism in general. Despite its military defeat it achieved a success of sorts coming so soon after the Act of Union by defying that very union. The language contained in his speech (Cowan Tracts) appears to be both derisory of the court of execution and equally dismissive of being portrayed as being an agent of France. It would appear that he curried no favour with France and went to his death in confidence of having served his country. Other notable figures that featured at that time were Anne Devlin, his devoted housekeeper who refused to divulge information to the authorities about him. For this she was tortured, her family incarcerated and despite pleas from Emmet himself she was not prepared to compromise. She would later die in poverty in the Liberties and the wall mural below is in her honour.

Sarah Curran

Sarah was the daughter of Jonathan Philpot Curran, a lawyer and politician, who had defended prominent leaders of the 1798 Rebellion He was initially unaware of his daughter’s engagement to Emmet and fell under suspicion by the authorities. However, Curran had represented other prominent Republicans in the past such as Wolfe Tone. He was appointed as Emmet’s defence but on being told by the authorities that his daughter’s association with Emmet could be construed as being complicit with the actions of his client, he had no alternative but to withdraw according to Hardiman (2005). His replacement, Leonard Mc Nally was in fact a Government spy Hardiman (2005) continues and received a special supplement to his secret pension for the betrayal of Emmet. Sarah Currans involvement apparently was that after his flight to the Dublin mountains, Emmet had been subsequently arrested in Harold’s Cross in August 1803 Dublin by the Chief of Police, Major Sirr. In his possession he had letters from Miss Curran with reference to the rebellion. In his attempts to prevent any harm or distress to Sarah, Emmet agreed not to call any witnesses on his behalf as long as the letters weren’t produced in court, Hardiman (2005) continues. By this method Emmet saved his sweetheart and accepted his faith.

Conclusion

Emmet will always be remembered for his 'speech from the Dock' and his undying love for his beloved Sarah. That remains an inspiring piece of verse, quoted by some in all manner of protestation, and by others as proof of an insurrection of the dispossessed, one could argue. People pay homage to the idealism of his cause; they cannot alas pay homage at his final resting place as this remains a mystery. He remains an enigma in that he took up the cause of the underprivileged and an idea that in essence his upbringing was opposed to. His speech was his defence against oblivion. He was executed on the 20th Sep 1803. All of the incumbents are long gone but the spirit of what they achieved; their connectivity with the events and players of that period in time and their desire for a better Ireland lives on. In the end as Hardiman (2005) opines the Crown got the leader of the Rebellion, McNally got his money, Sarah her immunity and Emmet his martyrdom.

"When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written".

- Robert Emmet.

Bibliography

Beiner. G. (2004) The Legendary Robert Emmet and His Bicentennial Biographers. The Irish Review (1986- ), No. 32, Thinking in Public pp. 98-104

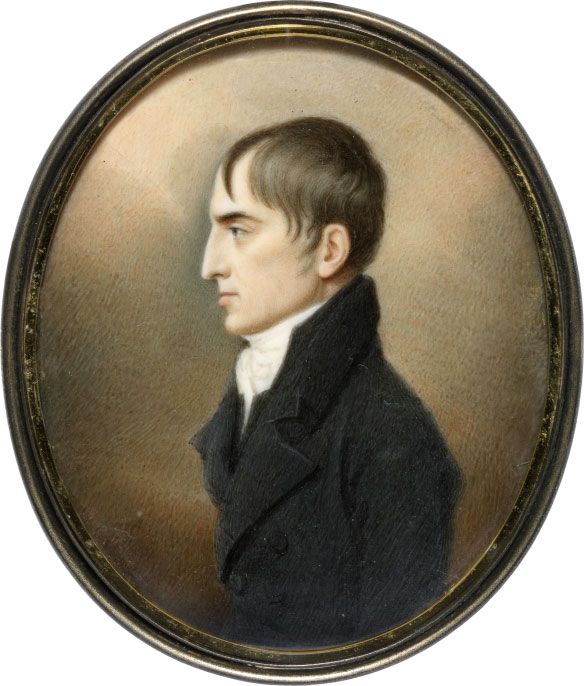

Comerford .J. Portrait of Robert Emmet.

Emmet.R. the Speech of Robert Emmet. Cowan Tracts, 19th Century British Pamphlets, Newcastle University, Cleaves of London, England.

Geoghegan P. M. (2003) Robert Emmet: A Life. Dublin Historical Record Vol. 56, No. 2 pp. 253-254 Old Dublin Society

Hardiman.A. (2005) The (Show?) Trial of Robert Emmet. History Ireland Vol. 13, No. 4 pp. 25-30. Journal Article Wordwell Ltd.

Moran .S. (2013) Great Irish People. Liberties Press, Terenure, Dublin, Ireland.

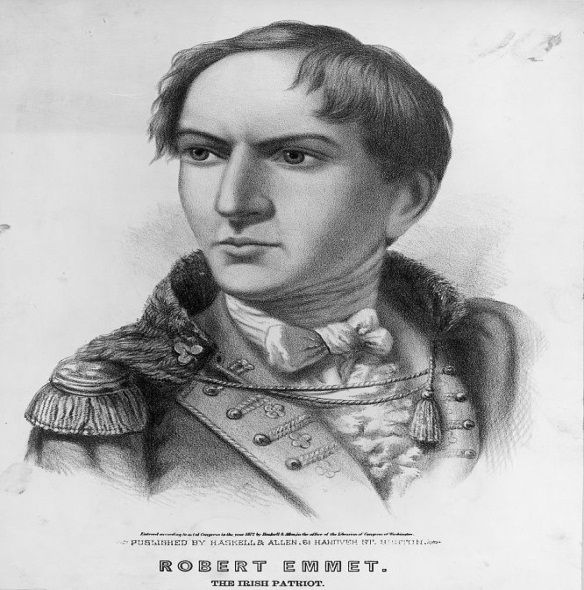

Haskell and Allen. Picture taken from a pamphlet two years after the death of Robert Emmet.

McGreevy.R. (2020) ‘His Grave is Ireland’: The search for Robert Emmet’s body. The Irish Times Dublin, Ireland.

Stone. J. (2003) Review: Robert Emmet: A Life. Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr Vol. 18 (2003), pp. 179-181 Eighteenth-Century Ireland Society

Whelan.K. (2003) Robert Emmet: between history and memory. History Ireland. Issue3 Vol.11

What You Can Expect

A walk through Dublin City in the company of a native Dubliner with the emphasis on history, culture and the great Irish ability to tell a story and to sing a song. In addition, and at no extra cost an actual rendition of a self-penned verse or perhaps a spot of warbling. I'd like to share my love of history with you, after all the past is our present and should be part of our future.

About The Tours

Tours are in English, with Irish translations, where appropriate. I also speak Intermediate level Dutch. Duration: 3 hours approx., with a short break in-between. Tour prices and booking options are available in the booking section.

The contact hours are Monday to Sunday, 09:00 - 20:00 IST.

Special Options

We can also arrange a half-day private tour for a maximum of twelve people. This incorporates a collection of parts of our three Tours combined. Tour duration 4-5 hours approx. A break for refreshments in between. Group of 2: €50 per person, Group of 3: €30 p.p., Group of 4 or more: €25 p.p. Refreshments: €10 approx. (This is an extra). Please contact us for details.

Copyright ©2025 Tailteann Tours

Designed by Aeronstudio™