An raibh a fhios agat? Did you know?

The Quakers and the Famine

In the course of writing anything about the Famine one is understandably touched by the awful human tragedy that befell our island and its people. But being objective is important in order to give a fair analysis or understanding of the tragedy. However, it is also worth recalling some of the people concerned in trying to bring help and succour to the poor of that period. Amongst that number were the Quakers or The Society of Friends. Though small in number and not having a real presence in the worst affected areas, in the West of Ireland in particular as it transpired, they were successful by all accounts in dispersing funds, clothing and farming essentials to the needy in the areas that they could reach. There are many facets and arguments about the causes of the Famine and of course responsibility for its coming. However the focus of this piece is to look at the efforts of the few to quell the tsunami of hunger that affected the many.

George Fox is credited as being their founder in England in the mid-17th century. They were derided in some quarters in England because of their refusal to sign the Act of Allegiance or to pay tithes. They didn’t attend at the established churches which also set them apart. Indeed some from the opposing side of the religious divide said that they were tarred with the name Quaker because they were have said to quake when brought before a magistrate. They would however earn the respect of many because of all of the charitable works that they engaged in not least in the Famine which would decimate Ireland. The Quakers came to Ireland in the 17th century primarily between the periods of 1650 to 1680 as settlers. Indeed William Edmundson having opened a shop in Lurgan convened the first meeting of the Society there in 1654. They were an industrious congregation by all accounts and were involved in diverse enterprises such as: Drapery, Linen, as shopkeepers and merchants. Those who remained in Ireland would later enter the world of high finance, shipping and the Coffey business etc. A number of those who refused to pay Tithes to the Anglican Church initially found themselves on the emigrant ship to America alongside many Catholics. But then came the Famine.

In order to coordinate its efforts in tackling the scourge of the Famine, a Central Relief Committee of the Society was set up on 13 Nov.1846. This in turn received support from its London office and also from America. The dispersal of the aid received would be the responsibility of Dublin with the areas selected chosen by London. To put this in context the total amount of relief provided from America was estimated at £150,000.The total realised from all strands of the Society was estimated at £200,000 initially for distribution by Dublin. This was a considerable amount of money back in the 19th century. How was this money accounted for? Soup-kitchens were set up in a number of areas noticeably in Munster where the Quakers were well established. Clothing was also distributed and attempts were made to set up small industry. Seeds were bought for the farming community and the retrieval of fishing equipment for fisherman in the Claddagh area of Galway who had had to resort to pawning this to survive was also accomplished. Such efforts while not always of long term benefit at least brought some succour in the short term.

At the height of the Famine there were essentially two issues that hampered the Quakers and their effectiveness in responding to the crisis: their numbers were quite small, a mere three thousand in a population of over eight million people and secondly that they were by all accounts non -existent in the areas most effected in particular in the West of Ireland. Some commentators give acknowledgement to the very diverse and wide spread of contributions that were made such as: The Choctaw Native Americans who donated $170 to Famine Relief in Ireland. In 1845 in India at a number of British Army bases, soldiers a large proportion of whom were Irish-born raised £14,000 according to Christine Kinealy in her book: Private Donations to Ireland during An Gorta Mór (1998).

In total she maintains that £1,000,000 was realised for Famine relied throughout the world. She tells of an interesting story about a Turkish sultan who donated £1.000. Several ships with provisions were also dispatched from Turkey to help in the relief effort. They were not allowed to land in Dublin so they landed at Drogheda with their precious cargo. Today Drogheda United soccer team wears a star and crescent on their jerseys in honour of Ottoman Sultan Abdulmejid I's assistance during the Famine.

Others make note of the fact that some relief came with strings attached such as: “souperism” which was a carrot to convert people to the Protestant faith. If one availed of the food or soup offered you were associated with the term ‘Souper’.The Quakers were by all accounts not so inclined. They were also opposed to violence but were not without their critics. There was for example a break away sect who called themselves the White Quakers. One of the difficulties they found was having to marry within the confines of their own congregation if you would. Whilst observing the main structures of the Quakers, they carried out charitable works, observed adherence to frugality but were also somewhat extreme if not different in their interpretation of modesty. They wore white clothes and painted their furniture such as it was also in white. In contrast they were also observed parading through the streets naked on occasion.

Quaker Businesses in Ireland

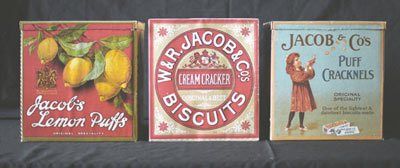

Today there are still a number of businesses and indeed other reminders of the Quakers in existence in the country that remind us of these people. Jacobs’s biscuits would be one such. Established initially in Waterford it opened as a biscuit factory in the capital in 1852. Some quarters point to the introduction of an employee welfare system that wasn’t the norm in the Ireland of the early 1900s.They employed 1300 people in and around this period. In contrast we learn that in 1913 during the 1913 lockout the company engaged in tactics that appeared to be very anti-worker. There was at the period in time an attempt by employers in Dublin to dissuade any of their workers from joining a Trade Union. Contrary to the welfare provisions as outlined earlier by Jacobs, other sources suggest that rates of pay were poor with long hours being the norm. The Lockout in 1913 would lead to a major confrontation with the workers Union the ITGWU (Irish Transport and General Workers Union) and the police culminating in the riots in Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) in which several of the protesters were killed by the police.

There was anecdotal evidence to suggest that some workers dismissed by their employers were told to enlist in the British Army to take part in the Great War. It was the case apparently that G.N. Jacob was one of a committee who oversaw the criteria as to how many men could be spared for this express purpose in Ireland at that time according to Lauren Arrington (2013). in REVOLUTIONARY GENESIS? JACOB'S BISCUIT FACTORY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF IRELAND. She goes on to say that this was seen by the workers as an attempt by employers to get rid of the more militant of their colleagues. Over time and as the 1916 Rebellion drew closer James Connolly the leader of the Citizen Army became more expressive in his attacks on Jacobs according to Arrington. Another company with a Quaker connection is Bewleys.

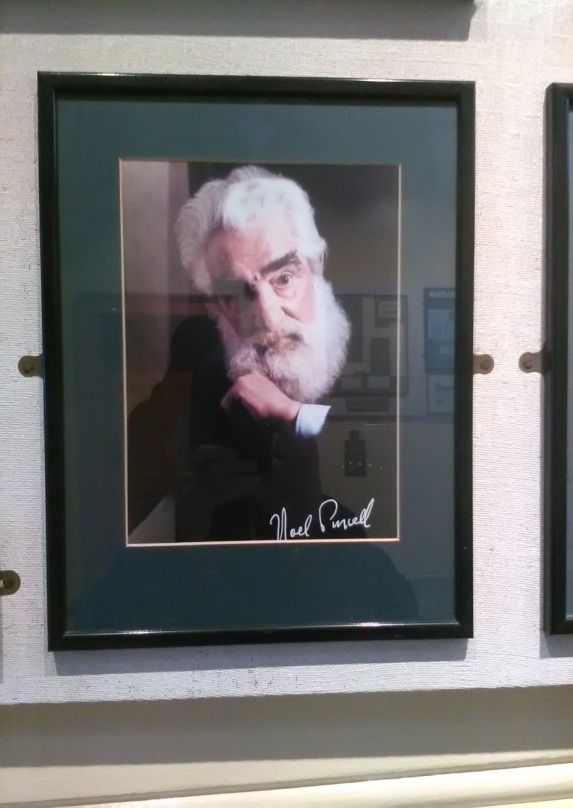

Bewleys established in 1840 is very much a part of Dublin folklore and a must do if you are a lover of good coffee. The premises on Grafton Street have long being a favourite haunt of Dublin’s coffee community. It is also graced by examples of the work of Harry Clarke as his stained glass windows beautify the already strongly scented décor as Dubliners enjoy one of their favourite beverages. The immortal words....’Dublin can be heaven with coffee at 11’ is perhaps most apt. The song is forever associated with a great old Dublin character by the name of Noel Purcell. Grafton Street is the place to be on a sunny day, sipping coffee at the emporium of pleasure and exploring the complexities of life that is all part part of the bonhomie of the sipping classes.

The shop on Grafton Street did close for a number of years back in 2004. It had an intermittent opening and closing saga that ultimately saw it reopening in 2017 after a major refurbishment. When one harks back to it’s predecessor and the great and the good that have inhabited it’s walls in particular, it’s resurrection was indeed welcomed by its many fans.This building was formerly Whyte's Academy grammar school which was established in 1758. Some of its past pupils were Oscar Wilde. Thomas Moore, Robert Emmet and the Duke of Wellington to name but a few. However, it remains as a landmark of the city’s history and its citizen’s aversion to coffee culture. The advice might be to pay a visit, sample the coffee, admire the work of Harry Clarke and soak in the atmosphere. If you want to sing however, you might have to ask permission.

Over time the influence of the Quakers would diminish as they resolved to interact more and more with modern society and effectively left behind their strict adherence to Quaker principles. This had a consequental impact on their number. According to Ahern (2003) in his article: The Quakers of County Tipperary paradoxically through their entrepenership and being involved in the commercial life of Tipperary in general and perhaps because of their work in Famine relief in particular, saw their number continuously decline. By 1924 it is estimated that only seven Quakers remained in what had once been a stronghold of their presence in Ireland. However, Desmond O’Neil in his article ‘The Quakers In Ireland estimated that from a high of 6.000 people in the 17th century the Quaker community numbered no more than 1.600 in the 20th century. Several thousand he goes on emigrated primarily from the North Of Ireland to Pennsylvania in the United States.

Jacobs have for many years been synonomous with biscuits and cream crackers. Some people might remember Woolworth’s store in Henry Street in Dublin. Reading a review of Maurice Wigham’s book The Quakers in Ireland reminds us of the treat of going into the store and buying the cheap broken biscuits an offering that came from Jacobs apparently. Then there is the story of poor people queing outside Bewleys of Grafton street who were given food which was the left overs of the day. On a more serious note he reminds us of the Quakers in Wexford who sheltered some of the Irish involved in the 1798 Rebellion at the risk of their own safety. A quote attributed to a Quaker is perhaps a fitting way to finish.

"Every country my country, and every man my brother."

Daniel Wheeler 1771-1840

William Edmundson was a Cromwellian soldier.

What You Can Expect

A walk through Dublin City in the company of a native Dubliner with the emphasis on history, culture and the great Irish ability to tell a story and to sing a song. In addition, and at no extra cost an actual rendition of a self-penned verse or perhaps a spot of warbling. I'd like to share my love of history with you, after all the past is our present and should be part of our future.

About The Tours

Tours are in English, with Irish translations, where appropriate. I also speak Intermediate level Dutch. Duration: 3 hours approx., with a short break in-between. Tour prices and booking options are available in the booking section.

The contact hours are Monday to Sunday, 09:00 - 20:00 IST.

Special Options

We can also arrange a half-day private tour for a maximum of twelve people. This incorporates a collection of parts of our three Tours combined. Tour duration 4-5 hours approx. A break for refreshments in between. Group of 2: €50 per person, Group of 3: €30 p.p., Group of 4 or more: €25 p.p. Refreshments: €10 approx. (This is an extra). Please contact us for details.

Copyright ©2025 Tailteann Tours

Designed by Aeronstudio™